BLOG

- Gepostet am

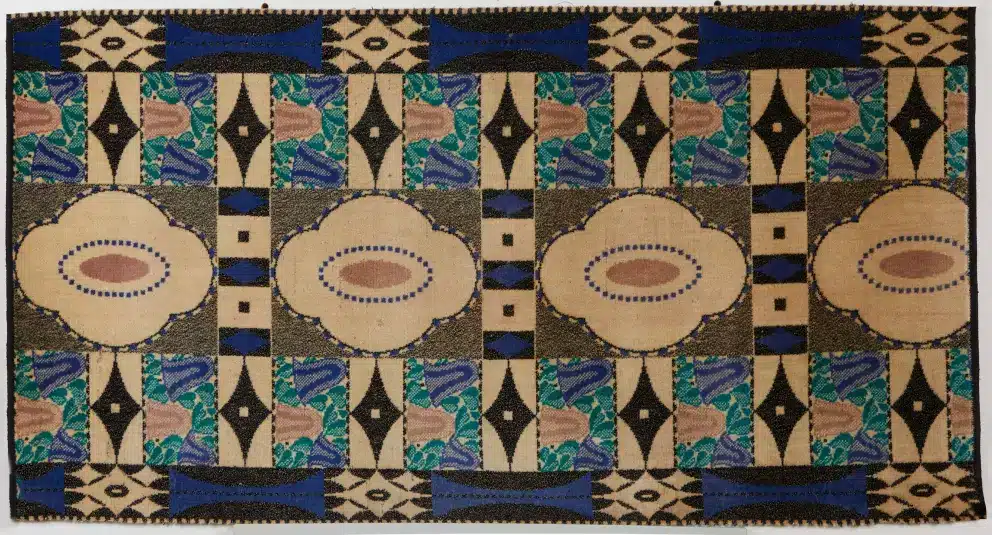

Otto Wagner, Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser and, of course, Josef Hoffmann were decisive for a new style that was to establish itself in Vienna. While Hoffmann and Moser founded the Wiener Werkstätte in 1903, a transformation and recreation in the style of art was generally in the offing.

Hoffmann and other artists and architects were tired of following the trend that had prevailed since the 70s of the 19th century, the historicism, (Neo-Gothic, Neo-Renaissance, Neo-Baroque, etc.) and turned away from it completely. The simple and practical should be the focus now. Geometry and clear lines were predominant. Future works of art, designs, but also buildings should correspond to the new geometric Art Nouveau.

One such building by Josef Hoffmann, designed and built in the years from 1906 to 1911, is the Palais Stoclet. It can be admired in Brussels, in the Brussels-Capital Region. The builder and client was the entrepreneur Adolphe Stoclet.

For this major project, for which Josef Hoffmann had already produced designs in 1905, he was to receive support from Gustav Klimt and other members of the Wiener Werkstätte. Klimt designed a golden frieze for the dining room of the palace. In art history it was to become known as the Stoclet frieze.

For the execution of the entire palace, very precious materials were used, such as Norwegian Turilim marble for the exterior walls and yellow-brown Italian Paonazzo marble for the interior walls. Hoffmann assembled the individual cubic structures with gold bronze strips. This created the impression of a weightless assembly of slabs. Today, Palais Stoclet is considered one of Hoffmann’s masterpieces.

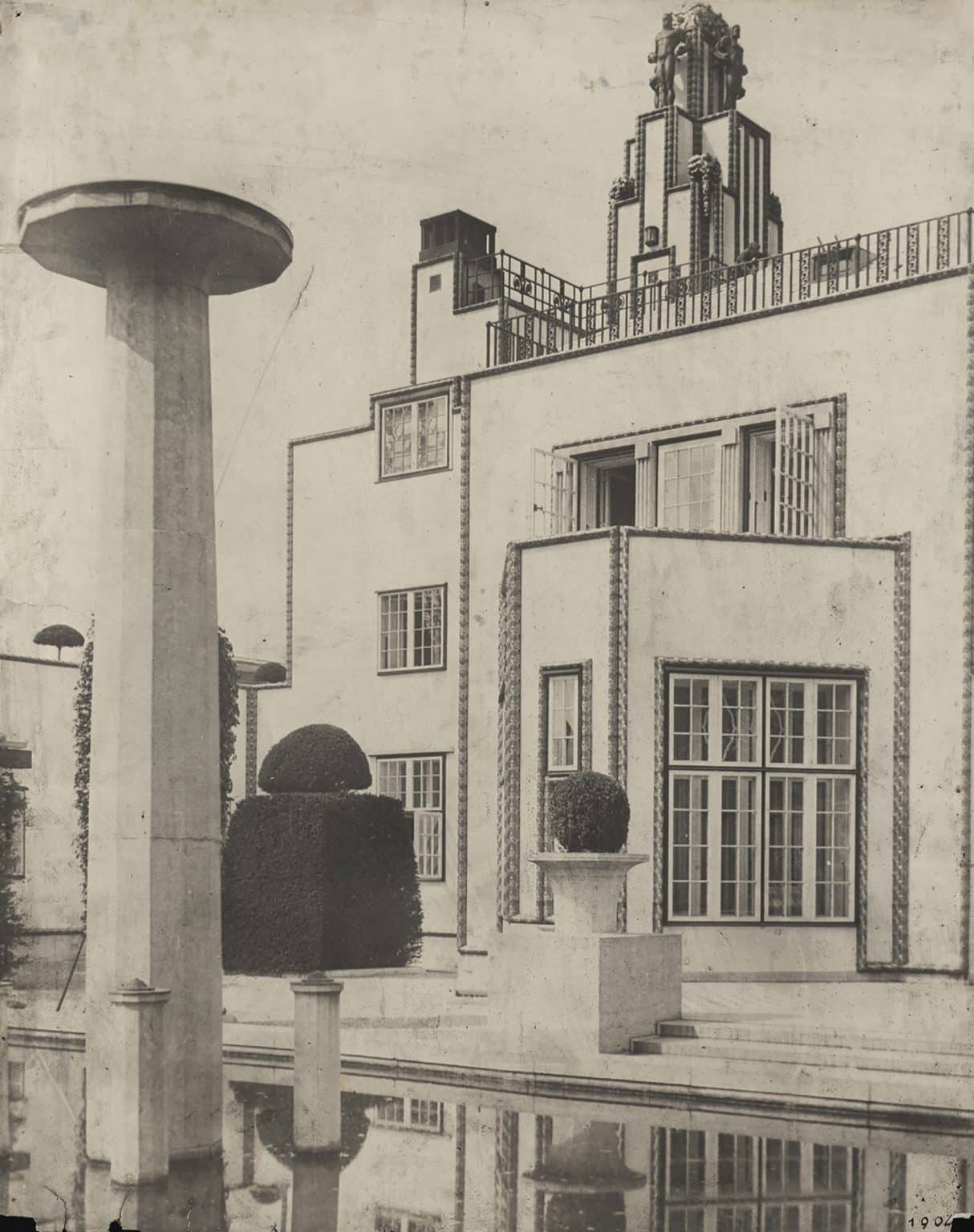

Another of Hoffmann’s buildings that achieved great fame and is not in Brussels, but in Hoffmann’s home country, Austria, was the Villa Primavesi. This Art Nouveau villa is located in Vienna, Gloriettegasse 14-16 in Hietzing.

This representative building was built from 1913 to 1915 for the industrial landowner and member of the Reichstag Robert Primavesi. Clear lines and large windows made the villa not only an inviting house, but also a successful architectural masterpiece of the time.

But it is especially Hoffmann’s Art Nouveau garden, which, together with the house, created a very special atmosphere. In the 1950s there was a redesign of the garden, but it has hardly been changed in its original form. As one of the most important garden architectural monuments in Austria, it is even mentioned in the Monument Protection Act of Austria.

After the Second World War, the villa changed hands several times. It was considered to be of such historical value that for some time it was even discussed as an official office villa for the Austrian Federal President. For a short time, the villa was considered for sale to the Bösendorfer piano factory. In 2005, however, it was finally acquired by the aluminum industrialist Peter König. He had the house renovated in accordance with the preservation order, but had an underground garage added for his classic car collection. To this day, Villa Primavesi is considered one of the most beautiful Art Nouveau villas in all of Austria.

- Gepostet am

Josef Franz Maria Hoffmann was a highly sought-after Austrian architect and designer. Together with Koloman Moser, he was a co-founder and one of the main representatives of the Vienna Secession and later the Wiener Werkstätte.

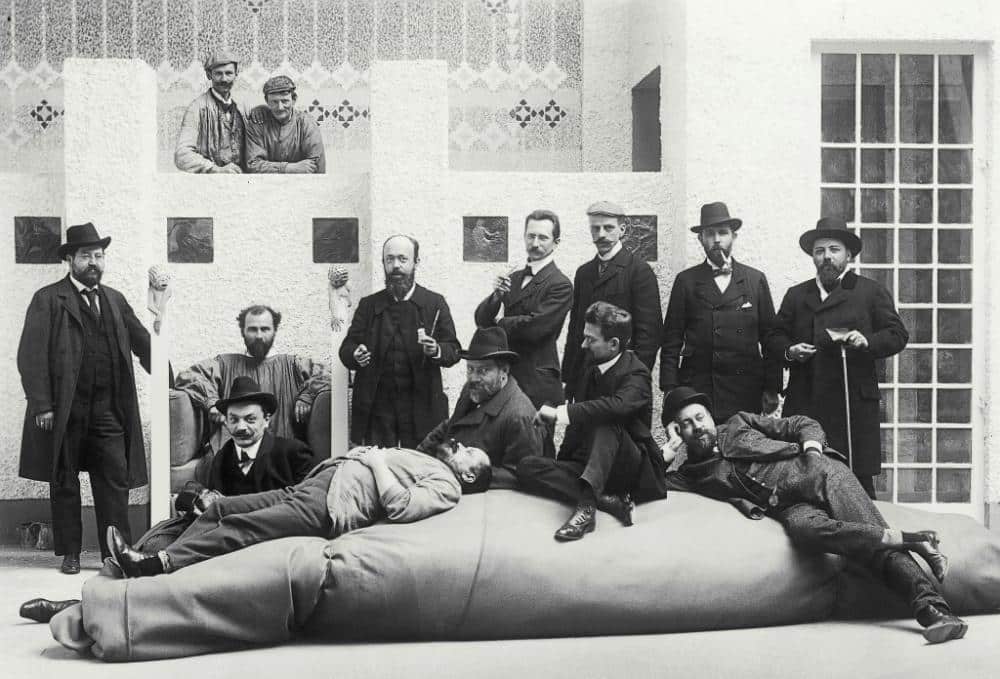

He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna under Karl von Hasenauer and Otto Wagner. In Wagner’s office he met Joseph Maria Olbrich. In 1897, together with 50 other founding members, they established the Vienna Secession. The president was Gustav Klimt. The Vienna Secession continued to shape Art Nouveau. Other artists and designers who also dealt with Art Nouveau who were not part of the Vienna Secession were the Hagenbund with Michael Powolny or with Loetz, to name a few.

The best example of this art movement in Vienna, from the fin de siècle period, is the Secession exhibition building built by Joseph Maria Olbrich. With its golden canopy, it’s still considered one of the most beautiful buildings in Vienna.

At that time, the call of the new art had materialized in an unmistakable and clearly visible way. The soft, flowing Secession style was a quick and great success.

As a founding member, Josef Hoffmann was also an important representative of the Vienna Secession. An example of this is an armchair that Hoffmann designed at the beginning of the 20th century. The client was the Jacob and Josef Kohn company. The armchair appeared in an advertisement by Kohn in the catalog of the 15th Vienna Secession Exhibition. In 1904, the beautiful piece of furniture was even presented at the World’s Fair in St. Louis in the USA. One of these armchairs was also on display some time ago in the Nikolaus Kolhammer art gallery.

In this modern interpretation of a fauteuil, Hoffmann refers to the curved shape of a horseshoe. The back section was formed seamlessly from a curved shell, using all the possibilities of bentwood technology. With this compact shell, Hoffmann gave the armchair a formal touch. However, he didn’t entirely forgo some discreet decorative elements. The arranged brass rivets and polished brass feet softened the simple design and gave the armchair an elegant playfulness. Hoffmann has designed a timeless, modern classic here.

But the Vienna Secession was soon to be replaced. For the artistic paths had already run in opposite directions in Vienna in the years before. The cultivated art of style, with its plant-like, ornate wealth of forms, was opposed by another conviction, rooted in the aesthetics of reason and practicality. The Wiener Werkstätte was soon to set the tone with a new direction of style in the visual arts, design and architecture.

- Gepostet am

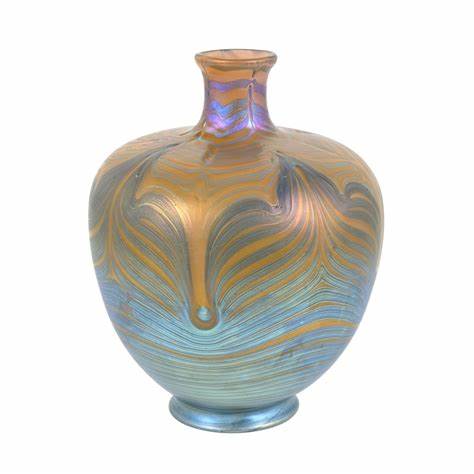

After the great success of the Paris World Exhibition of 1900, the Loetz company experienced a great economic boom. Naturally, glassblowers created new and extraordinary vases, which followed the decor of the world exhibition.

One of these vases, made between 1900 and 1902, also belonging to the “Phenomen Genre”, is known by its name pattern 802. It is signed “Loetz Austria”, is 21 cm high, 16 cm wide and just as deep.

Some decors are combined with different shapes of vases, and as a result, similar variants were created. This one is different. In the case of the “Phenomenon Genre” 802, the present decoration is applied only to this vase shape. It is extremely rare. Only a few copies are known. Two of them are in collections of museums. One is in the Bröhan Museum in Berlin, the other is in the Passau Glass Museum. Another is privately owned and one in the Kunsthandel Nikolaus Kolhammer.

The decor is exceedingly complex and of exceptional beauty. The vase has a light pink ground (Loetz internal designation “metal red”). On the surface cobalt blue are spun, and in the upper part, silver-yellow oxide strings. After that, while still hot, they have been warped upwards and downwards with tongs, transformed into four symmetrical feather patterns. The resulting surface of the artwork looks almost like a beach with shallow water. As if in the glow of the Southern Sea sun, blue tones shimmer from light blue to turquoise and purple at the vase opening. One could almost believe that the beach and the shallow sea of a Southern Sea island have been spun onto a Loetz vase.

Overall, the classic and elegant vase shape beautifully accentuates the very complex and playful decor. It is a masterpiece of the Loetz workshop after 1900.

A completely different vase from 1901 is particularly striking with its tall twisted shape. Originally, Christoph Dresser designed this vase for another glass firm. Loetz decided to include it in its production program around 1900. It is signed ,,Loetz Austria” and known under the name Dekor Phänomen Genre ¼.

The 32 cm high vase stands out especially due to its tapering shape towards the top. In addition, large drops of varying lengths emphasize the dynamics of the twisted glass body and form a unique contrast to the uniformly warped, horizontal decor. Shimmering silver, almost pearly, covers an orange and rust red. Those colors reminiscent of a sunrise.

Another vase, made around 1902, belongs to the decor “Argus” and is one of the most popular variants from the family of the phenomenon genre. Silver oxide patterns create the impression of ice blue eyes on a rust red background. With spun silver eyelet threads, this Loetz-owned design is one of the most sophisticated decorations.

Here, the Bohemian glass manufactory was strongly oriented and inspired by the Secessionist style. The style refers to a group of artists, including Gustav Klimt, which at the time, represented the aesthetic avant-garde of Vienna.

The shimmering silver particles seem to float as if they are moving on a water surface, with the bluish wave-like silver threads undulating and giving the pattern a uniform dynamic. The spun-on decoration is particularly beautiful on the hazel ground, which graduates downward to a lighter hue.

It is called decor ,,Argus” because the pattern is reminiscent of eyes. Argus is a giant from Greek mythology, who had eyes all over his body. Even when he slept, some eyes remained open and could vigilantly observe everything around him. When Zeus was looking for a new lover and his choice was Io, his jealous wife Hera, had Io guarded by Argus so that Zeus would not seduce her.

However, the king of the gods sent Hermes to Argus, who was no match for his divine powers. Hermes killed Argus and Zeus seduced Io. Hera took pity on Argus and made him immortal. She put all his eyes on the plumage of the peacocks. From now on, these were to be protectors and companions of the Queen of Olympus.

Thus, like the beautiful plumage of peacocks, shimmering blue and green, Loetz vases also bear the divine attributes of Hera, making them all the more immortal objects of art.

- Gepostet am

The hard work of Spaun and all his collaborators ended in great success. Critics and the press praised his glass vases to the highest degree. The Grand Prix of the World Exhibition was a prize that had previously only been awarded to greats such as Gallé or Tiffany. Hofstötter and Prochaska were also honored for their work. In addition to all the successes, the 1900 Paris Exposition naturally also brought great economic success for the Loetz company.

Another vase with which Loetz made a breakthrough at the World’s Fair was the decor Phenomenon Genre 384. This vase was not known when the new book by Ernst Ploil and Toby Sharp was published. (Lötz 1900, by Ernst Ploil and Toby Sharp, in Kinsky editionen) Before that, only the pattern cut was known. When it did appear, its dimensions corresponded exactly to the scale on said pattern cut. It was also probably a Loetz decoration. Compared to other Loetz vases, this one is quite large and crafted in a floral and Art Nouveau-like shape. Due to the elaborate craftsmanship and especially the artistic iridescence, this work became an exceptional object.

The decoration consists of a multitude of layers of green, brown, white, and blue threads, which were spun onto the still unblown value piece, which was then artfully warped. This unique blend results in the golden shimmer of the vase, a flowing pattern that transitions from light green to golden yellow and light brown tones. In addition, darker streams run across the surface of the decoration. These create a playful rhythm that gives the vase a special beauty.

At a cost of 70 francs, the vase was one of the most expensive pieces offered at the time in terms of price. The elaborate decoration harmonizes perfectly with its considerable size. This workpiece, like Genre 387, ,,Pink with Silver”, is another example of the Loetz workshop’s glass art. They were supposed to outshine Tiffany’s much more expensive glass objects at the Paris World’s Fair, and they succeeded.

- Gepostet am

After Max Ritter von Spaun, grandson of Susanne Gerstner, took over the company in 1879, the firm achieved considerable economic success, but the artistic and international reputation it sought failed to materialize. The company’s own designs were too one-sided, and there was a lack of artistic influence from outside.

But all of this was to change with a new corporate strategy. Spaun had articles written for art magazines in which he presented the latest creations from the glassworks. With the intention of raising the company’s profile, he also gave away selected glass creations to museums and influential entrepreneurs.

Finally, the emerging collaborations with major institutions such as the Vienna School of Applied Arts (Wiener Kunstgewerbeschule) and the Viennese artists’ associations Künstlerhaus and Secession were decisive. Particularly noteworthy was the collaboration with major Viennese glass manufacturers such as J. & L. Lobmeyr and E. Bakalowits Söhne.

In 1896, Austrian companies were able to apply for the upcoming Paris Exposition (Exposition Universelle), and Spaun did everything in his power to obtain permission to participate. In March 1896, the time had finally come: the Johann Loetz Witwe glass factory received an acceptance for the world exhibition.

Over the next four years, Spaun changed Loetz’s entire commercial and artistic strategy. His goal was a successful participation in the Paris Exposition. It was not the only exhibition Spaun participated in during these years, but it was probably by far the most important. Especially in the years 1898 to 1900 several new glass processing methods as well as color variations, chemical as well as technical achievements were pushed. Many of them were also registered as patents.

At the same time, Spaun followed the work of the U.S. glass manufacturer Louis Comfort Tiffany with great enthusiasm, whose “Favrile” glasses were exhibited in several European cities. The iridescent glass captivated both Europeans and Spaun. The great success of American “Favrile” glass inspired Spaun to produce iridescent art glass himself in his glassworks. This was not prohibited by copyright at the time. He demonstrated to the world that Loetz could produce iridescent art glass of the same high quality as its international competitors.

But Spaun did not want to simply copy the international trend and added his own, more modern touches. His vases were based on traditional forms, which he modified with twists and wavy patterns. For the designs of the world exhibition collection, Spaun commissioned a rather unknown artist: the young South German painter Franz Hofstötter.

Hofstötter was to design 100 vases for the 1900 Paris Exposition. It was important to Spaun that, on the one hand, the technical innovations of his glass factory be emphasized and, on the other hand, that modern, unusual vase shapes be the focus of Hofstötter’s designs. Decisive, and what Hofstötter also excelled at, were his designs for the iridescent surface decoration. The patterns were intended to reflect the Central European trend but convey a very unique artistic and modern interpretation.

In addition to these aspects, the color scheme of many glass vases was also new. Eduard Prochaska (Loetz’s managing director) was decisive in this regard. Due to his knowledge of glass technology and craftsmanship, he and his employees were able to decide exactly how Hofstötter’s creative ideas could be put into practice.

Overall, the collection for the World’s Fair stood out strongly from earlier Loetz vases, including some glass bowls and plates. While there were some glass objects that were not entirely new in terms of technology, form and color, and were reminiscent of older models, many of the exhibits were exceptional and innovative.

Undoubtedly, the decor Phenomenon 387 Pink with Silver belongs to one of these vases. It is signed and is one of the most famous works by Loetz, which was on display at the Exposition Universelle.

The shape and decoration of the 47 cm high vase were penned by Franz Hofstötter. To capture such a complex decorative design on such a large vase was a challenge even for the master glassblowers of the Loetz Witwe company. The successful execution was the best example of the workers’ master craftsmanship. The exhibition phenomenon Genre 387 was explicitly developed for this form design. This can be deduced from the same number of pattern cuts and decor.

The characteristic work of Franz Hofstötter is the typical naturalistic and symbolic surface design. The base of the vase, which is kept in a dark tone, can be understood as earth. The transition into the blue and silver-yellow threads that meander along the body of the vase like currents of wind is interpreted as air and atmosphere. As a subsequent finish, the rest of the vase is orange-red and represents the heavenly fire. All those elements, earth, air, and fire, are prerequisites for creating iridescent glass and must be skillfully combined to create such a work of art.

With a creation like this, the art glass of Louis Comfort Tiffany should be eclipsed. Loetz succeeded in doing just that. It was this vase in particular and other ones that brought him not only the highest award, the Grand Prix, at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, but also his international breakthrough.

- Gepostet am

Already in the 1930s, wooden art objects were produced at the Werkstatte Hagenauer in Vienna. But it was especially the 50s in which wooden figures became more and more popular.

After the Second World War ended, the situation at the Werkstatte Hagenauer returned to normal. Brass parts and objects were no longer recycled for armor but were once again used to make art objects and household items. Slowly, the economy began to stabilize once more. In addition, Franz Hagenauer returned from the war.

In the post-war period, a lot of wooden furniture was also in demand. Franz managed to convince his brother Karl to open a second branch at Mirabellplatz in Salzburg, and in addition, a wood turnery in Fuschl am See. There, many pieces of wooden furniture were produced, and the well-known animal figures were created from smaller pieces of wood.

In the beginning, they especially produced many cats, dogs, birds, horses, and different forest animals, such as foxes. Walnut and maple were the most used wood species. During the 1950s, exotic motifs became more and more popular in Austria. It was a kind of wanderlust, because times in Europe were still hard. People associated tropical places and their fauna and flora with harmonious emotions. Moreover, people imagined distant parts of the world as natural paradises where there was always summer.

While the workshop also began to make figurines of Africans, Indians, and Asians from a variety of materials, it was also the wooden figurines of exotic animals that were particularly popular with many customers. Polar bears made of white maple, elephants made of walnut, leopards made of precious wood, or springboks and gazelles were just some of the animals from distant lands that the workshop turned and partly carved.

The depiction of most of the animals is highly stylized and reduced. The shapes of the animals are clearly worked out and easy to recognize. Apart from the ears and noses, however, other details are mostly not elaborated. The animal figures reflect a reduction in the formal language, as it is known in the Werkstatte Hagenauer.

One such exception is the panther on the tree, made of walnut around 1950. The size of the wildcat and the tree stump on which it rests also make the animal figure a rarity from the Hagenauer Werkstatte. The depiction is highly stylized as usual, though some details are finely carved. The ears are clearly rounded. The paws, the muzzle, and the mouth are clearly highlighted.

Overall, the combination of the dark animal body and the lighter wood of the branch creates a beautiful contrast. An additional effect is created by the slight reflection of the wildcat and branch in the polished brass at the base. The viewer can directly imagine the predator above the water enjoying the evening sun in the jungle. This extraordinary figure merges an elegant design with a high-quality finish, which awakens wanderlust in any viewer.

- Gepostet am

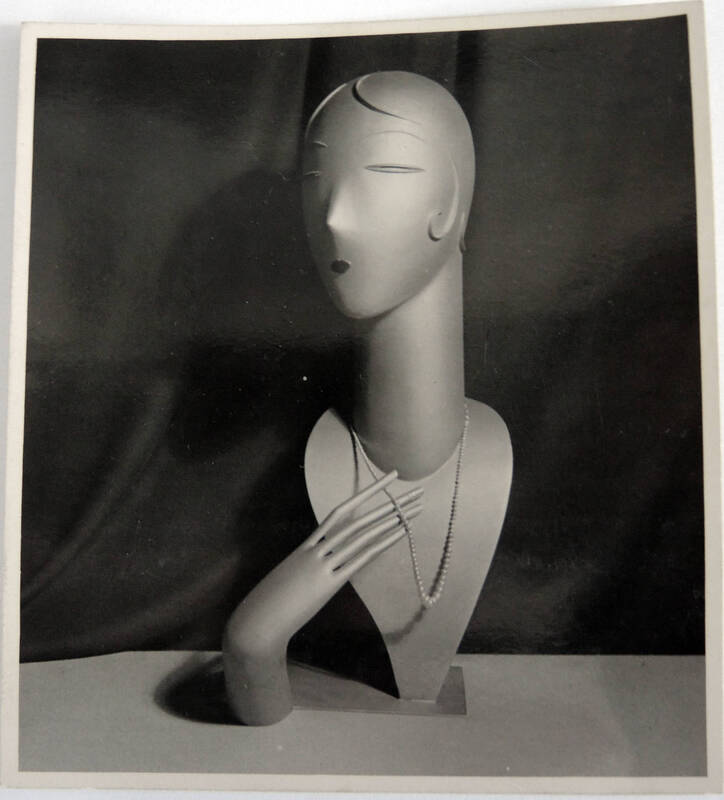

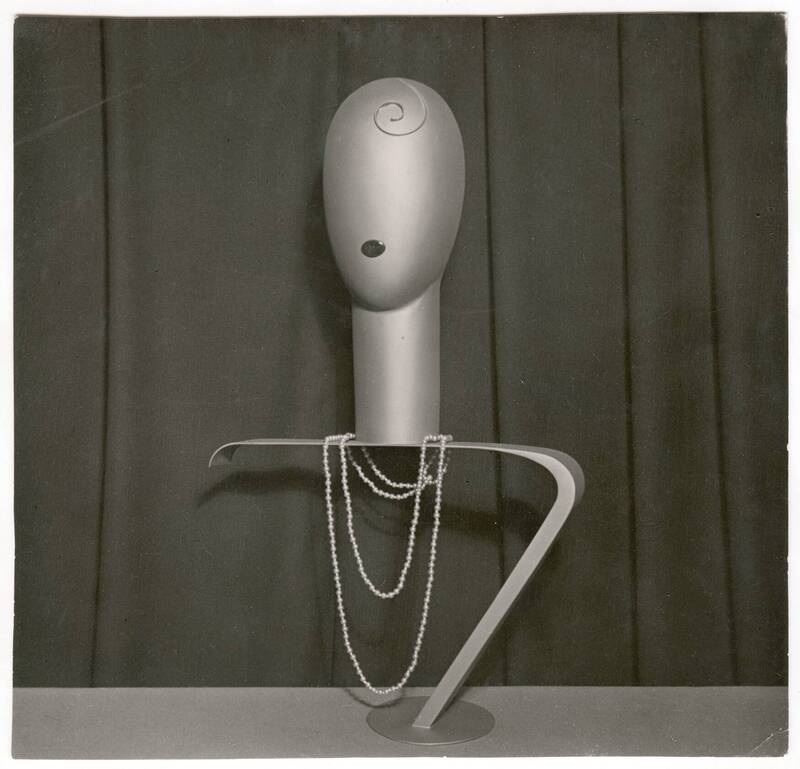

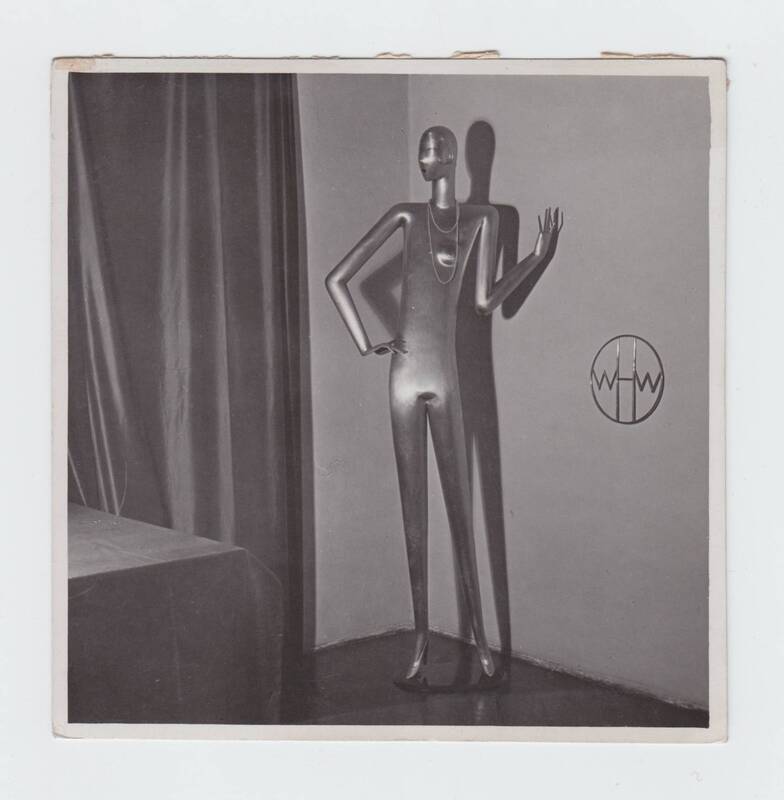

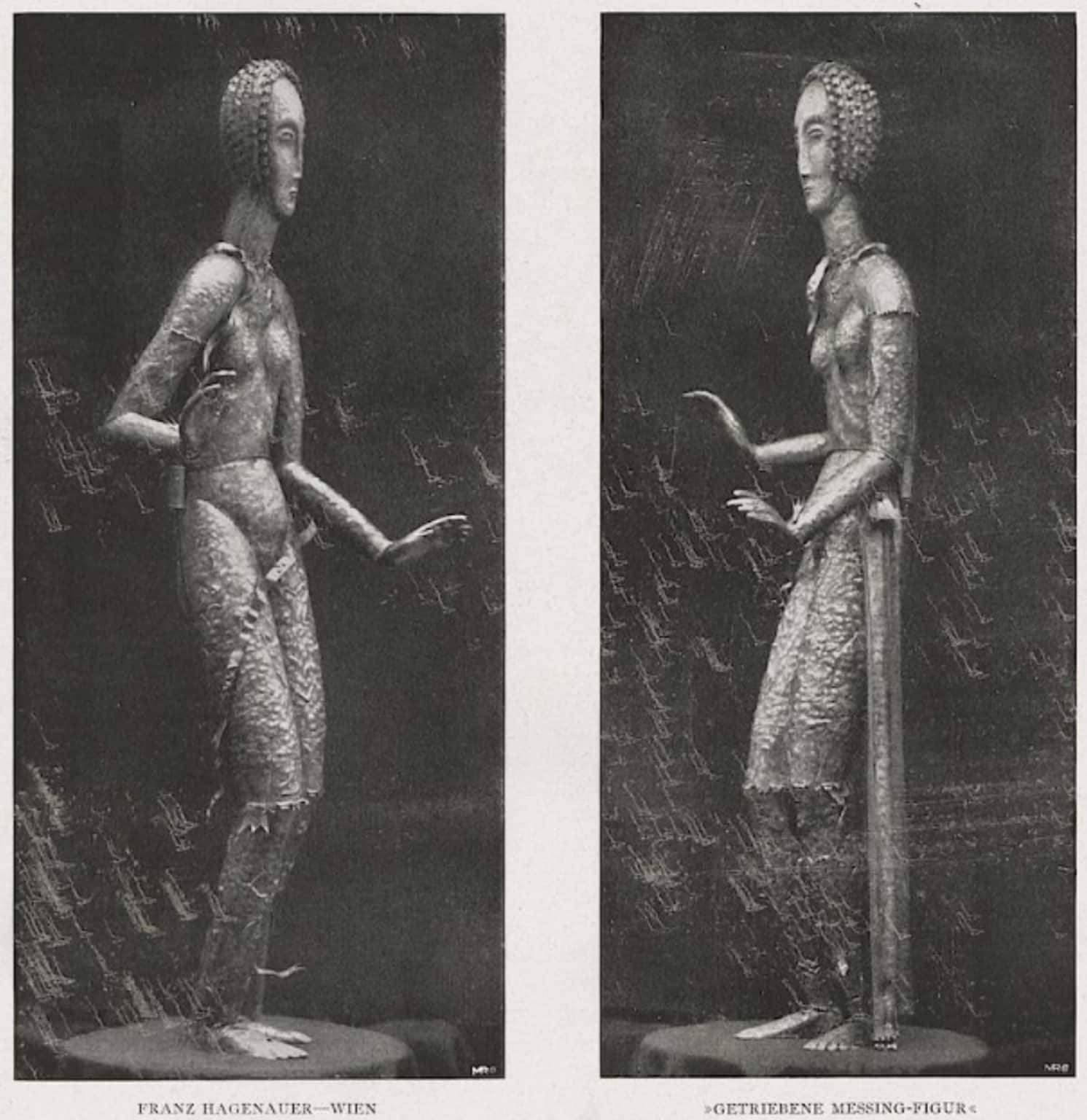

In 1971, as part of the retrospective, the MAK (Museum of Applied Arts) presented works from the interwar period, the origin of which can be attributed to Franz Hagenauer. These busts and life-size figures had already gained popularity since the 1920s, which were sometimes used as window-shopping decorations. Compared to industrially manufactured mannequins made of plastic, the busts and figures were valuable individual pieces. Overall, they were also designed in an avant-garde design, which speaks for their uniqueness. The small model busts, often made with hands and fingers, were popular with jewelers. They decorated them with rings, necklaces, bracelets or watches. These pieces were art and functional objects at the same time.

Much more rarer were life-sized, almost oversized full-body models, so-called “mannequins”. Some of them were even over two meters tall. A model made of alpaca, for a client from abroad, is said to have cost the equivalent of over 4700 euros, and thus belongs to a very expensive object for the time. Such figures were reserved for exclusive customers on request.

In the 70s and 80s Franz Hagenauer took up the life-size models and busts again. They were adaptations of the figures from the 30s. However, their formal significance dwindled and their practical utility was nullified. They became their own class of new works of art from the House of Hagenauer. They were sculptures of an elegant past recreated and adapted for a new time.

Such a large sculpture from 1970 is the “Life-size trumpet player”, which is 183 cm high. Made of bent and chased brass, it expresses the masterful workmanship of the Hagenauer workshop. The Trumpet Player embodies a dedication to art that emulates the passion and talent of its master, Franz Hagenauer. With great attention to detail, Franz Hagenauer designed the musician’s wardrobe with delicate chasing and with protruding applications, which thus appear particularly vivid.

Another masterpiece of the great figures of Franz Hagenauer is the ,,Life-size piano player“. Here Hagenauer succeeded in reducing the physical features to a flat, almost two-dimensional plane. This type of design is particularly characteristic of the late creative period of the Hagenauer workshop.

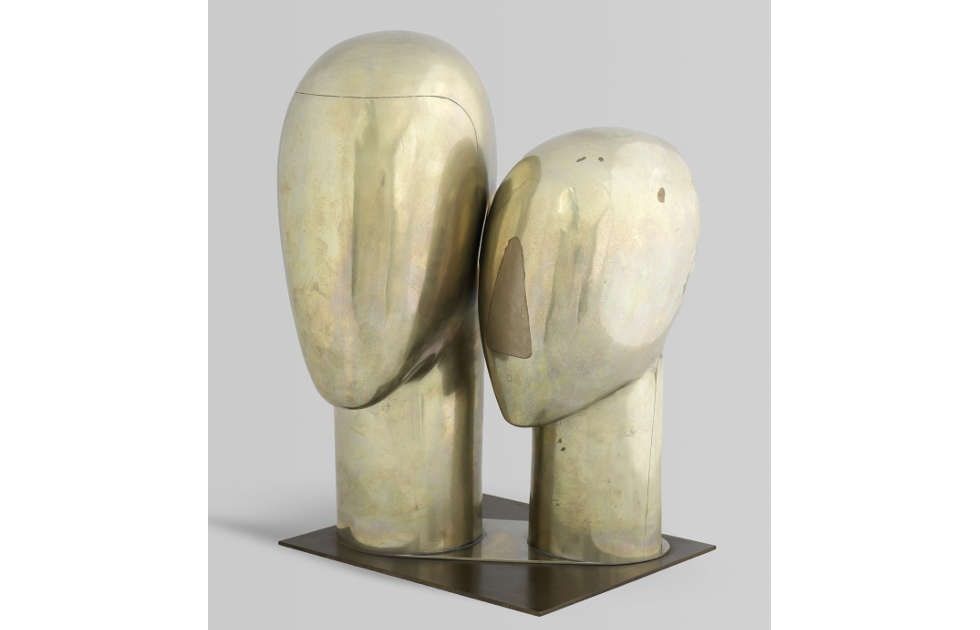

A bust from this late creative phase is the “Large Double Bust” and was probably created around 1980. It is also based on models from the interwar period. In this double bust Franz Hagenauer placed two female heads next to each other. The two inclined heads, cheek to cheek in intimate unison, almost touch each other and radiate a close bond. In this work Franz Hagenauer’s qualities as a sculptor, which he acquired over the decades, come to the fore.

Masterfully chased from a single piece of brass, Hagenauer retained the futuristic character and further developed radically reduced heads here. He loosened up the appearance of the sculptures with attributes such as the stylized nose section and the flowing and wavy curls. With this late work Franz Hagenauer designed a sculpture of strong charisma and in a sense closes the artistic circle from his sculptural beginnings to the mature work of his old age.

- Gepostet am

In 1931 Franz Hagenauer’s name as a metal sculptor first appeared in the ,,Lehmann’s Allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeige”. He was located in Bernardgasse number 7. in the seventh district as a metal sculptor. As mentioned in a previous blogpost (Franz Hagenauer and the dream of the sculpture – kolhammer.com), it was his big dream to become a sculptor. A dream he was able to turn into reality.

Especially at the end of the 1920s and at the beginning of the 1930s Franz Hagenauer began to create his famous head sculptures, which were to accompany him throughout his life.

Two very early documented works by Franz Hagenauer, semi-plastic heads made of alpaca, probably date from 1928, and are marked with the monogram ,,FH”. For a long time one of them was in the collection of Andy Warhol, but found its way back to Austria through the art trade. They are now both in the Leopold Collection and two of the first chased heads by Franz Hagenauer.

Another object, which is dated even earlier, is a head sculpture, and was probably made between 1925 and 1930. This figure may have been created as part of the 1925 Paris World’s Fair. At that time Anton Hanak and his students, including Franz Hagenauer, created a so-called “cult room”, which was filled with works by the students.

This head most likely belonged to the special ”cult room” as well. As with other works, the workmanship here was extremely elaborate. Wrought brass, copper and enamel were used here. Characteristical for an early piece are the highly detailed worked facial features.

In contrast stands a key work from the 1930s. The double head, made of alpaca, shows an extreme reduction in the abstracted head shape and the facial features. This work points the way for many upcoming pieces by Franz Hagenauer, which he would produce until the 1980s. It is inscribed with ,,FRANZ”, the monogram ,,HF” and with the number ,,36” which probably indicates the year of its creation.

A similar work from the same period is a head with a standing collar. Masterfully wrought from a piece of alpaca, it shows the design power of the young Franz Hagenauer and his sculptural qualities. Inspired by the contemporary avant-garde and futurism, here he radically reduced the anatomical forms, and stereometrically condensed them to an ovoid head and a cylindrical neck.

Thus, the unadorned head appears archaic, and its uncompromising reduction gives it a timeless radiance. The only design elements on this hermetic male head are the suggested hairline and the reduced ear. The only visible decorative accessory is a stylized collar.

- Gepostet am

Compared to other materials, brass was easy to clean and, above all, had a much lower purchase price. The Werkstatte Hagenauer achieved a much broader clientele through a great many brass products.

In comparison, the Wiener Werkstatte came under increasing criticism, especially after the First World War. The philosophy of the Wiener Werkstatte, its exclusivity, and the target group of the rich and big industrialists seemed outdated. Especially in the post-war period, when society and politics were undergoing major changes throughout Europe and America. Critics of the Vienna Art Show of 1920 described the Wiener Werkstatte as outmoded and not adapted to the changed political and social conditions.

The Wiener Werkstatte was blamed for still depending on decoration and ornament. They were criticised in 1925 by the contemporary critic Armand Weiser for being ‘one for the display of excess and luxury’.

This contrasted with the Werkstatte Hagenauer, which greatly reduced ornamentation. Their creations did not get lost in ornamentation. This was to the advantage of the Werkstatte Hagenauer. They were praised as pioneering. They fulfilled the changing artistic and social requirements of the time.

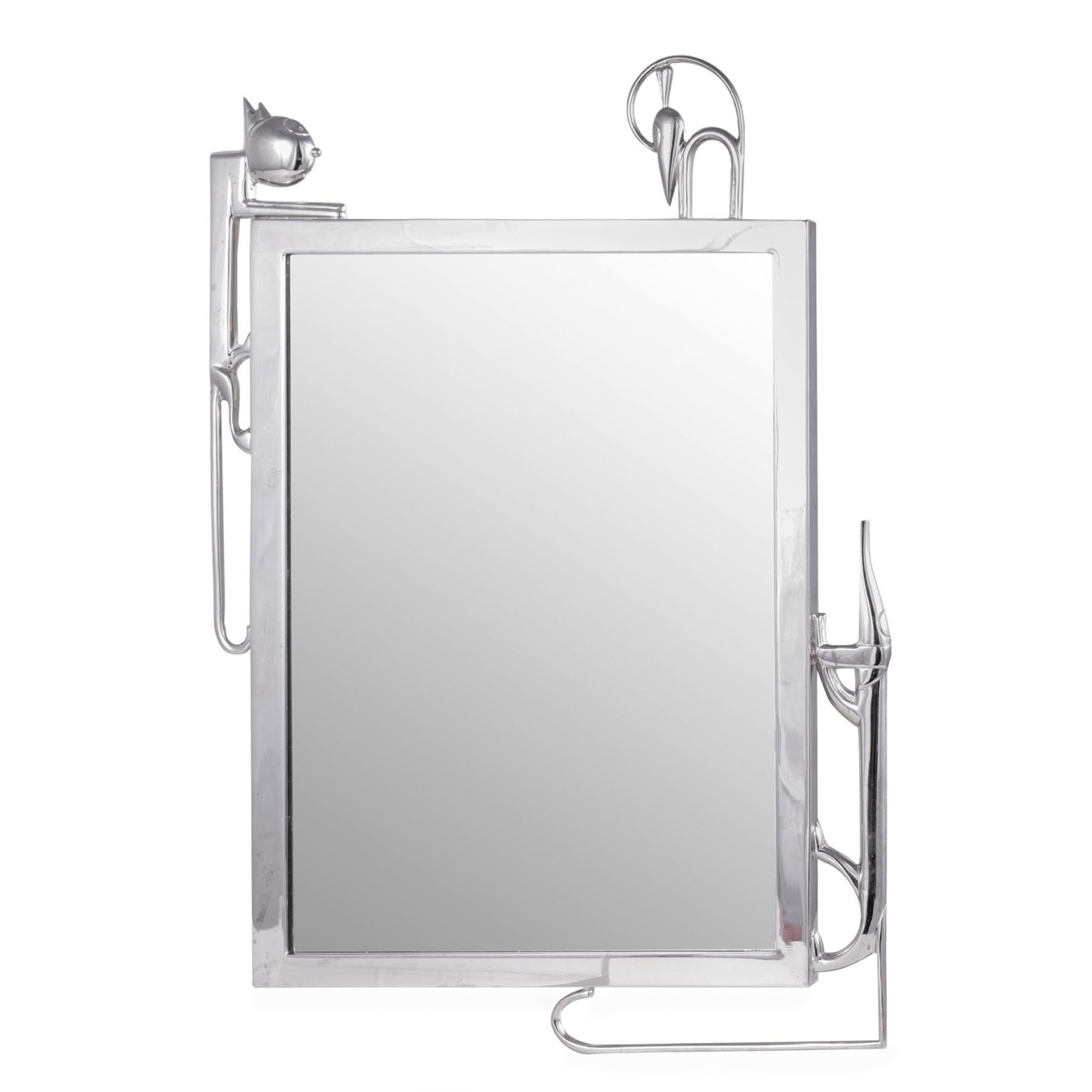

A very fitting example of this was a mirror titled: ‘Dog, Cat, Mouse’ which was designed around 1930. The mirror frame shows an exciting chase of the three animals. With an exceptionally fine sense of humour, Karl Hagenauer designed such witty episodes, which charmingly decorated some of his objects. The comic-like and reduced details showed Karl Hagenauer’s mastery of stylistic reduction, for which the Werkstatte Hagenauer was to become famous.

Another aspect that benefited the Hagenauer workshop was the flexible price range in which the objects were offered. There were works of art and objects for everyone to buy. For four shillings, you could buy a beautiful ashtray. For 18 shillings, an elegant bookend. But there were also objects like a magnificent chandelier for 320 shillings or a large floor lamp for 600 shillings.

Critics were continuously fascinated by the pieces of the Werkstatte Hagenauer. Weiser, for example, wrote the following in a 1925 issue of Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration: “Each of their pieces is of consummate workmanship and reproduces all the merits of an easily mastered technique in form and colour. By hammering out and leaf-like trimming of the curved edges, silhouetting is repeatedly achieved.“

As this report showed, the execution of a design and the skill that goes with it is of extraordinary importance. It was the quality of craftsmanship that was very inspiring. These technical and work-related backgrounds were also important aspects of exhibitions. At the Paris World Exhibition of 1925, the Hagenauer workshop was represented with designs by Karl. His objects were awarded medals for their technique and craftsmanship.

- Gepostet am

The 1920s were a time of economic boom, and this was also reflected in the Werkstatte Hagenauer. Bowls, cans, and various utilitarian objects such as inkwells, writing sets, candlesticks, table and floor lamps, or mirrors were produced in large numbers.

In these years, Karl Hagenauer orientated himself towards ornamental and formal styles. Here he followed the trend set by the Wiener Werkstatte, Josef Hoffmann or Dagobert Peche. At the same time, however, he also created objects that have the typical recognition value of today’s well known Werkstatte Hagenauer : Geometric contours and pure forms are dominating, whereas functionless ornaments began to disappear.

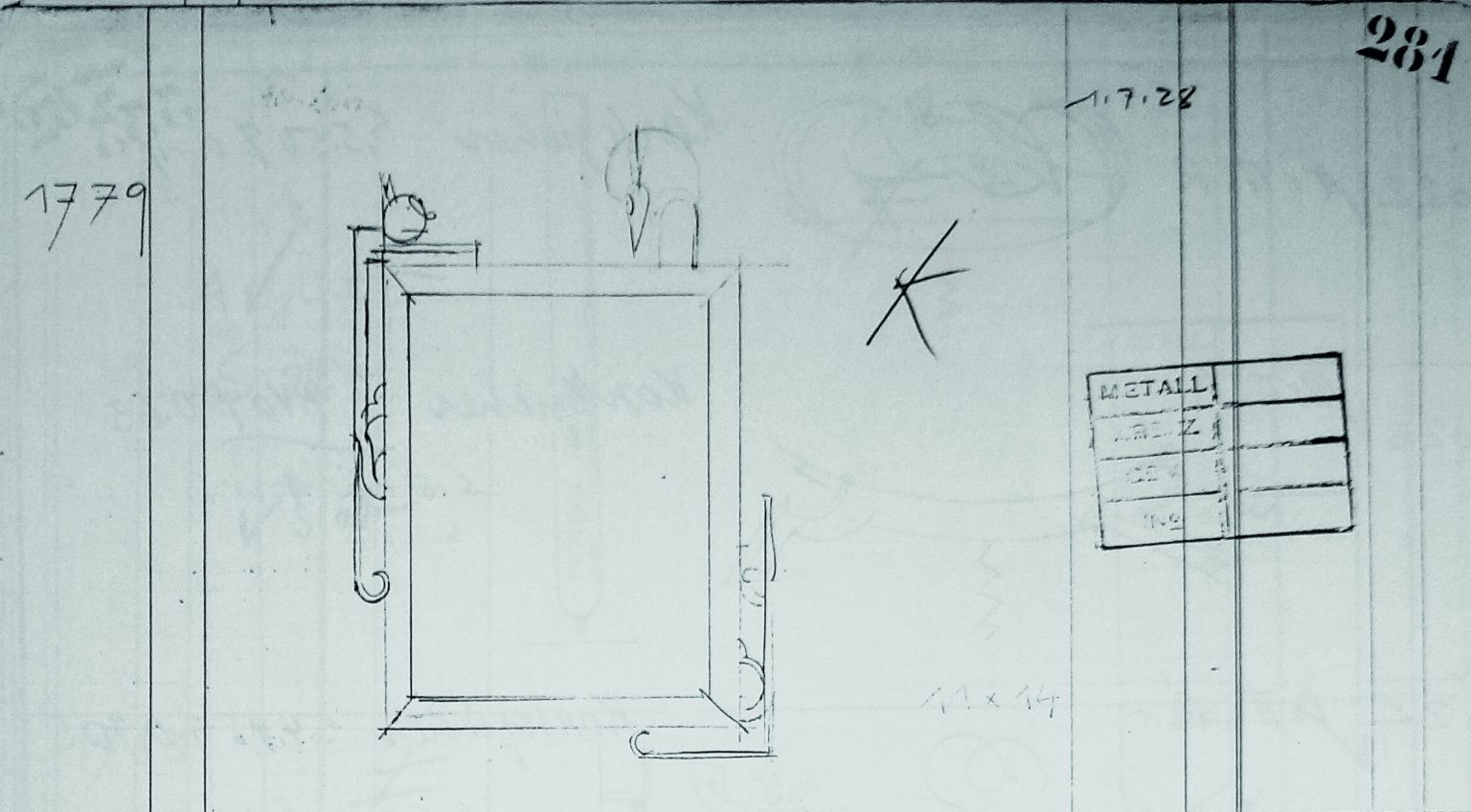

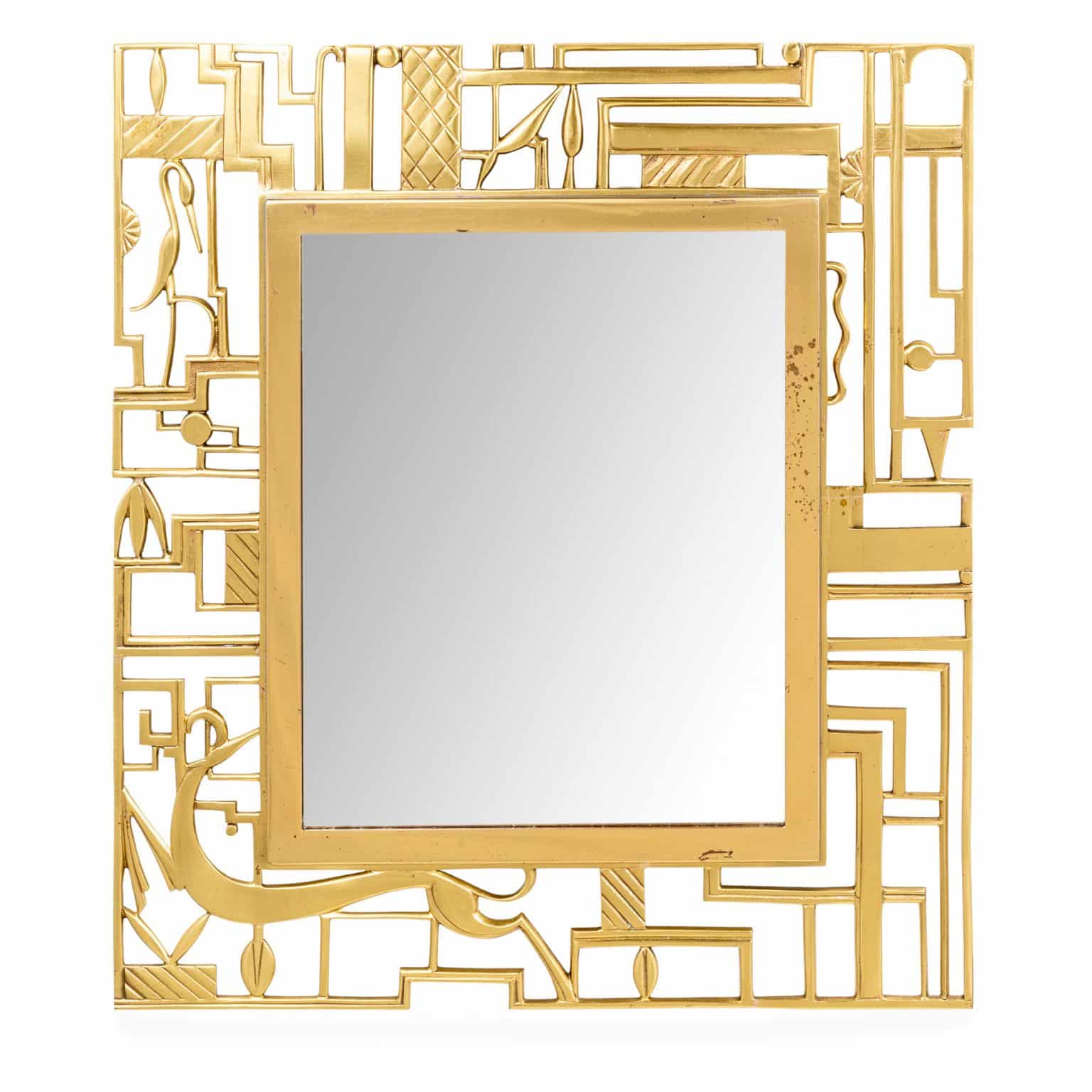

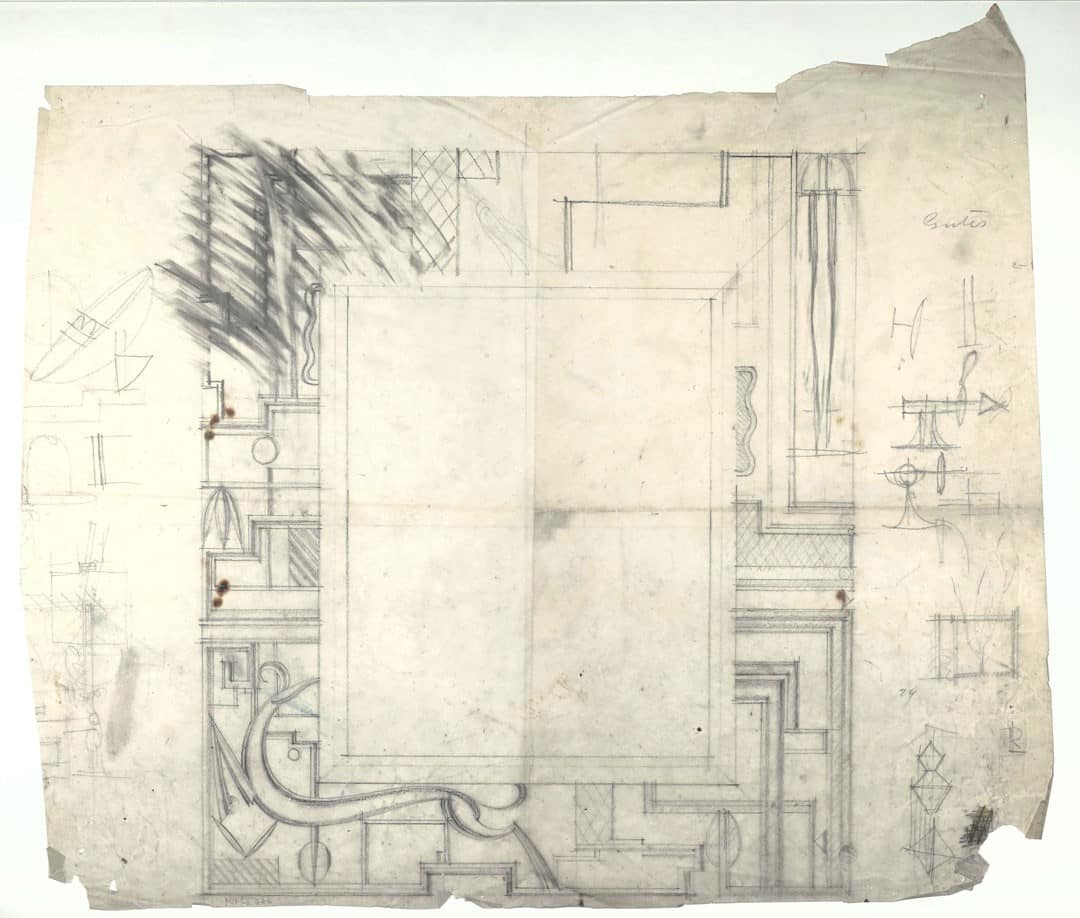

One such example, which could be described as a transitional work, is an ornamental wall mirror, from around 1928. It is the design of a decorative mirror. The frame is decorated with geometric elements and stylised animal figures in an openwork technique. Between the reduced floral and geometric ornaments, a dog, a heron, and a bird are clearly visible. Their soft lines lighten up the strict composition of the frame.

The formal language is strongly reminiscent of the influence of the Wiener Werkstatte. Especially when it comes to depictions of animals, one recognizes the imaginative ornamentation that was very much the style of Dagobert Peche. At the same time, however, there is a clear development towards reduction in figures and ornamentation. A style that was to become characteristic of the name Hagenauer and would later stand for the Werkstatte.

This direction was also particularly evident in some vases, jars, and bowls. In particular, larger animal figures, which were of course limited to decorative purposes, left many decorations in their appearance behind. A playful elegance, enhanced by form and little decoration, became characteristic under Karl Hagenauer’s leadership and reflected the changing times.

But it was especially the materials that reflected the historical period in the Werkstatte Hagenauer. Alpaca, copper, and above all, brass was among the materials predominantly used. Brass products were particularly popular. The ornamental wall mirror mentioned above is also made of brass.

There were also different processing methods for this material. On the one hand, there were chased brass plates or chiselled objects, and on the other hand, there was the sand-casting process. Here, the objects were subsequently polished to a high gloss.

- Gepostet am

Like his older brother Karl, Franz Hagenauer attended Franz Cizek’s highly sought-after youth art course in Vienna. When he began his regular studies, he had a clear idea of his future. Early on, he knew exactly what he wanted. On the application form under career aspirations, he wrote: Sculptor.

But it was still a long way until then and Franz Hagenauer had to overcome some hurdles. Franz was influenced by the Czech cubists, who often worked formally with prisms and pyramid vocabulary. Other influences during his student years were expressionism and kinetic art. During that time Franz worked a lot on plaster cuts, ceramics and chasing works. However, he was initially given only a “Satisfactory” grade by Cizek during his time at school.

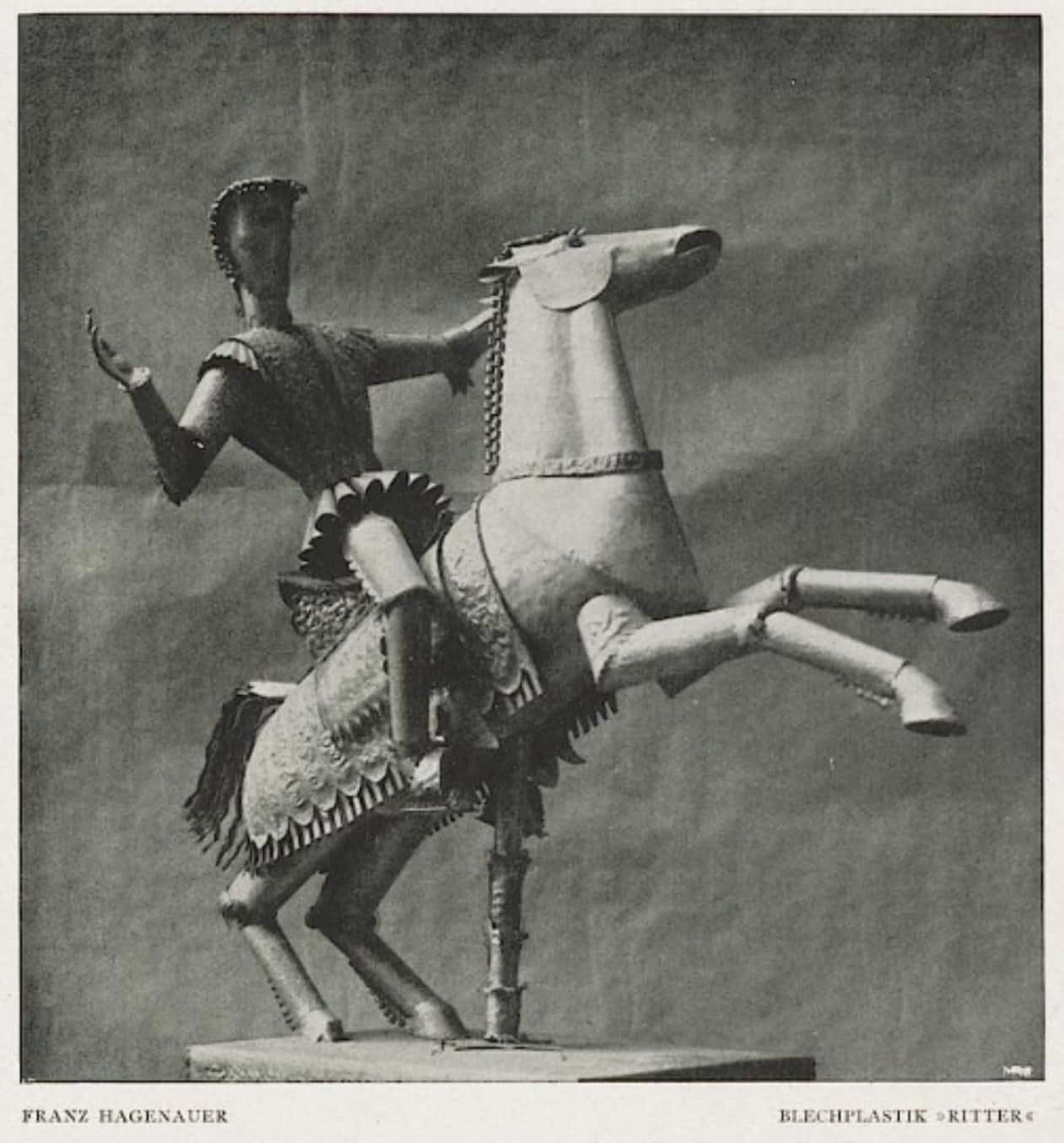

But his first great success was not far off. Further training followed under the sculptor Anton Hanak in Vienna. And in the school year 1922/ 23 he received a prize of one million crowns (today about 670 euros) from the Wiener Werkstätte in a competition for a brilliantly crafted sheet metal sculpture.

In his last year at school, he also took a course in belt-making, repoussé and chasing with Josef Hoffmann. Since Hoffmann immediately recognized his talent, he was not only taught by him but was also allowed to work for him. This was a great honor for the young sculptor. However, he attended this course for only a few weeks, as he was released from work for the Paris World Exhibition of 1925. For now, he had finished with his studies. After difficult beginnings, success and requests for work came flooding in. Nothing stood in the way of his dream of becoming a professional sculptor.

In the same year, however, Franz Hagenauer suffered a minor setback. An article about the Hagenauer workshop appeared in the trade magazine ‘Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration’, in which sheet metal sculptures by Franz were strongly criticized.

But this was immediately followed by praise for the exhibits at the Paris World Exhibition. Together with other students of Hanak, a “Room of Metals” was presented in Paris. This was described by critics as a sheet metal workshop, praised as a “cult room”, and was lauded as an example of passion of a professional way of working.

Success at the World Exhibition was followed by a period of work and further study for Franz. In the late 20’s Franz began working in the family business. There is uncertainty when exactly he began working at the Hagenauer workshop, as only a few pieces were explicitly signed with his signature mark. Moreover, while working for the family, he did not lose sight of his goal to become a sculptor. In 1928, he officially began training in the belt-making trade. This is why works by Franz Hagenauer for the Hagenauer Werkstätte from the late 1920s are very special.

One of these pieces of work from that time (around 1927 to 1930) is also currently offered in the Nikolaus Kolhammer Gallery. It is a brass bowl, cast brass, wrought, and chased. Figures in long robes are depicted. Their gestures, praying and praising, indicate Christian saints. On some of these figures, halos can also be seen. However, other figures are not to be overlooked in the bowl. One of them, for example, is a rider on horseback, which could also be the image of a Christian saint.

Floral elements, which are geometrically arranged, and stylized animals connect the different episodes of the sacred figures. It is fascinating how religious with more profane motifs are related to each other here. Benedictory figures, courtly horsemen, animals, and floral elements are combined to create a stylish overall image of an excellently crafted brass bowl.

The inspiration for this bowl by Franz Hagenauer can be traced back to work for the 1925 Paris World Exhibition. As mentioned earlier, Franz exhibited pieces with other students of Franz Hanak in the “cult room”. Many of those works show patterns similar to the brass bowl, combining sacred scenes with secular motifs.

This brass bowl is an excellent testimony of a young, promising artist who, after hard work and minor setbacks, continued to focus on his goal and was able to apply what he had learned. The bowl is a testimony that Franz Hagenauer became a great sculptor.

- Gepostet am

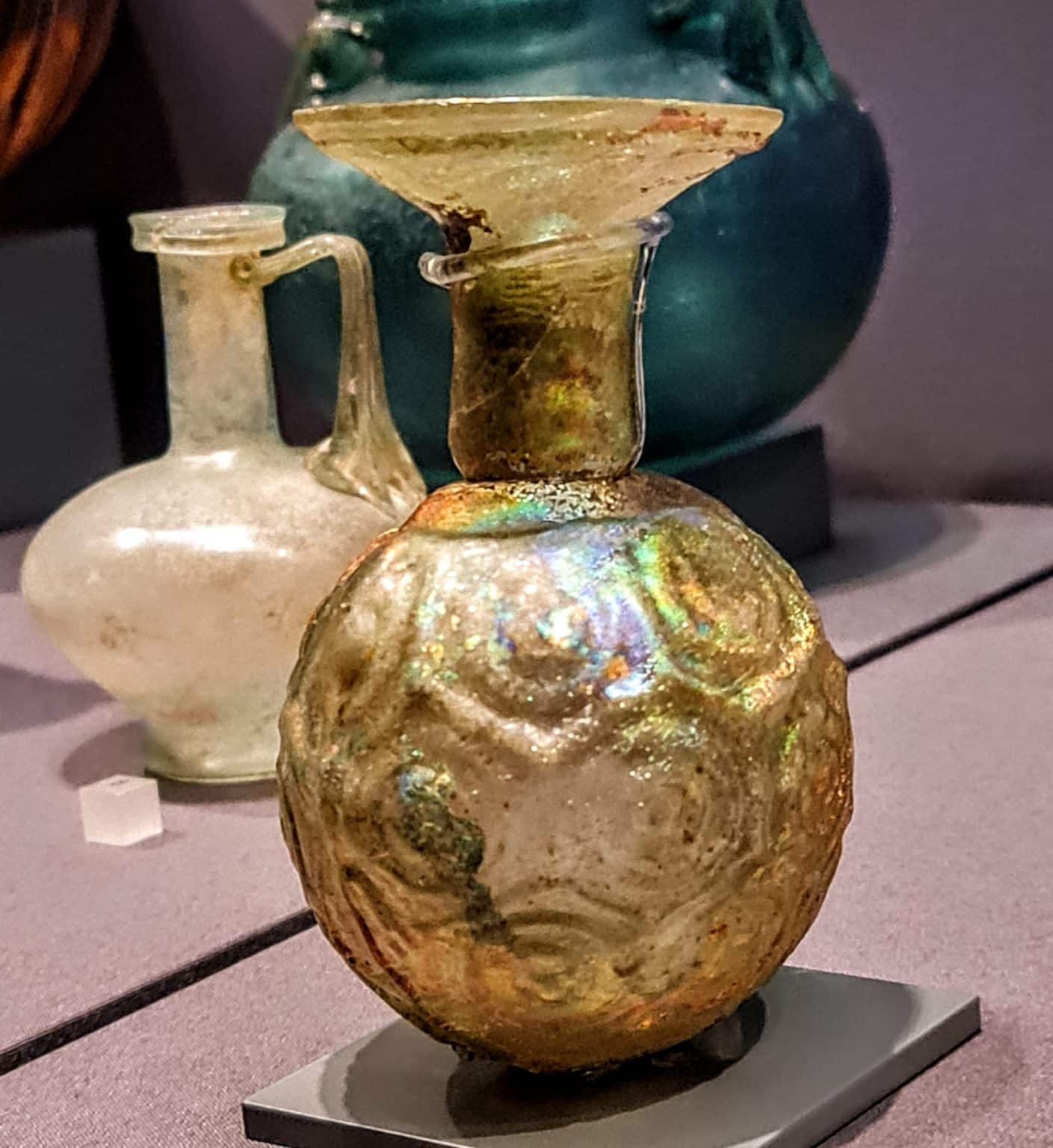

Loetz vases have a long tradition that has changed many times since the 19th century, and the glass art itself has an even longer history. Back in ancient Egypt, over 3000 years ago, glassblowers made vases that are not dissimilar to the Loetz vases of today. The ancient Egyptians produced glass and glass vases from quartz mixed with plant ash in furnaces. Most of these glass vases were made in blue, the color of the Nile, the life source of the Egyptians. However, the glassblowers also succeeded in the difficult production of red glass. Here the glass had to be fired in an environment without oxygen so that the copper did not oxidize and turn blue. The production of red and blue glass was a sacred art among the Egyptians. The recipe of glass production was also known as “the secret of the pharaohs”. And, as the name suggests, glass vases and glass jewelry were reserved exclusively for the pharaohs.

Just as ideas, themes and motifs from nature were adopted in the production of Loetz vases, such as the shape of flower calyxes or the patterns of blossoms and plant leaves, so too did the ancient Egyptians adopt forms from nature in their glass vases. At that time, however, the patterns had a closer resemblance to leaves, were less colorful and were kept in the colors beige, yellow or brown. But the basic idea of the Egyptians was the same as that of many glass artists of the 19th and 20th centuries. Shapes and colors from nature were adopted and captured in glass art.

In the 19th century, historicism was predominant in glass art and Loetz was also dominated by historicism at first. It was not until much later that those simpler forms, inspired by nature, would prevail. In 1879 Susanne, Johann Loetz’s widow, handed over the company to her grandson, Maximilian von Spaun. Together with Eduard Prochaska, he modernized the company and introduced innovations and new techniques to the glass art of historicism. For example, intarsia glass, octopus glass or the very popular marbled glass, which imitated the appearance of precious stones.

Successes and prizes followed in Brussels, Munich and Vienna, as well as at the World Exhibition in Paris, the Exposition Universelle, in 1889. However, the great success did not come. And to this day the Loetz glass vases from the period of historicism are less in demand and are also traded as less valuable.

It was in 1897 when Maximilian von Spaun first admired Tiffany Favrile glass in Bohemia and Vienna. Its great success did not go unnoticed by him and he decided that the Art Nouveau style was the direction in which Loetz glass should also develop to.

The next years, until the turn of the century, were to be Loetz’s most successful and artistically exciting years. The glass factory produced a new generation of glass vases. The inspiration for the vases was to be found in nature itself. Vases like calyxes, implied petals, or meandering shapes like rivers decorated the iridescent colored glass. Fanciful vases, many shimmering like opal, were created at that time.

With the new style Loetz also collaborated with very famous artists, such as Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, the Wiener Werkstätte or Franz Hofstötter. All of them created designs and sketches for Loetz vases. The highlight of this collaboration was in 1900 when Loetz made history at the Paris World Exhibition. Along with Tiffany, Gallé, Daum and Lobmeyr, Loetz won the Grand Prix. The company received the award for the Phenomenon Series, created in collaboration with Hofstötter.

In the Nikolaus Kolhammer Art Gallery, a Loetz vase, designed by Franz Hofstötter for that very Paris World Exhibition in 1900, was also offered and sold recently. It is the Exhibition Phenomenon Genre 387 ,,Pink with Silver”. This vase is a typical example of Hofstötter’s designs, as the surface design is inspired by nature. All the elements, earth, air and fire, which must be united to create iridescent glass, are represented in the vase. The base of the vase, in dark brown, is held in the color of fertile earth. This is followed by woven, flowing threads in silver and light blue that meander along the vase. They are interpreted as air and atmosphere, which are followed by more orange and pink threads that can be seen on the vase like fire itself, giving it an almost glowing impression.

- Gepostet am

In the middle of the 19th century, Emperor Franz Josef I ordered the bastions of the first district to be dismantled to build the magnificent Ringstrasse. From 1858 to 1874 Vienna was a huge construction site and during that time the world-famous buildings of today’s Vienna Ringstrasse were built, including the museums, the theatres or the City Hall.

It was a time of prosperity and all these new projects offered artists and craftsmen many opportunities for work. The Viennese arts and crafts experienced an unprecedented heyday. There was also a technical breakthrough in bronze casting. The costly lost-wax casting process was replaced by the sand-casting process. This meant that the casting mold remained intact and a figure could be recast indefinitely. The economy flourished and from then on bronze and iron objects could be mass produced on an industrial level. The rising and increasingly wealthy middle classes were paying customers.

Almost at the same time, Carl Hagenauer began his apprenticeship at the Viennese silverware factory Würbel & Czokally. He received a classical education in historically oriented designs, especially the Renaissance. The silverware factory specialized in “decorative art objects” such as centerpieces, bowls and cups.

After completing his apprenticeship with the master goldsmith Bernauer Samu in Bratislava, he not only founded his first workshop in the economic center, but also a family.

A few years later, however, he and his family were drawn back to Vienna, where he opened his own workshop at Zieglergasse 39. The clientele in Vienna and the opportunities that unfolded at the turn of the century were simply more abundant in the capital.

At first, he designed classical Viennese bronze ware based on models from antiquity, the Renaissance and the Baroque. It was everything that corresponded to the taste of the time.

But with the advent of Jugendstil in Vienna, Carl Hagenauer found his true passion. Asymmetrical design and flowing lines, the characteristic elements of Jugendstil, found their way into his craft. From then on, Carl Hagenauer produced bronze figures, reliefs and lamps in this increasingly popular art movement. Not only in Vienna, but throughout Europe he became one of the most sought-after artists in the metal-working arts and crafts scene.

Carl Hagenauer enabled his children to build on his success and provided them with the best possible education. His son, Karl, was enrolled in the School of Applied Arts. There he attended Franz Cizek’s popular youth art course. In 1912 Karl began his regular studies in architecture and was taught by masters such as Josef Hoffmann. But in 1916, like all young men in Europe, Karl too, could not outrun his fate. He was drafted into the military, but quickly found himself in Italian captivity, and when he returned to Vienna in 1919, he was able to finish his studies.

After successfully completing his studies, Hoffmann commissioned his former student to create objects for the Wiener Werkstatte. He designed a large number of ivory objects, which were made by a carver in Hagenauer’s workshop. Due to their ornamental density and style, the resulting creations were very reminiscent of Dagobert Peches and were also erroneously attributed to him for some time.

The product range of the Hagenauer workshop grew rapidly in the 1920s. In addition to tin boxes, bowls or writing sets, candlesticks, table and floor lamps were now also produced and sold. Among them are a pair of candlesticks, which are currently on sale in the Nikolaus Kolhammers Gallery. In 1928 they appeared in the sales catalog, but since they are not yet marked with the typical company signet ,,wHw” in a circle, they could be dated to 1920.

The pair of candlesticks, made of solid brass, are an excellent example of what Karl Hagenauer oriented himself by in the period after the First World War. Geometric patterns and the curved shape of the candlesticks go hand in hand with the ornaments. Those stylized animal figures and the flower-like designed spouts are reminiscent of the works of Dagobert Peches. In the formal language, the influence of the Wiener Werkstatte is clear.

At the same time, however, geometric contours are already asserting themselves in this work. Moreover, the pure form of the candlesticks begins to dominate over the functionless ornament. Here, the animal figures are entirely decoration, yet they appear elegant and playful, in harmony with the pair of candlesticks. The uniformity of the feet and arms already indicate early Art Deco design, they are a wonderful example of Karl Hagenauer’s early style.